‘The challenge for intelligent, sensitive folk is to take over’

Shy and depressed in his youth, Bob Brown went on to become a major figure in Australian politics and a pioneer for the environmental movement. I chatted to him recently in Hobart.

By October 2003, the war in Iraq was 7 months old. Amnesty international had released a report revealing the torture, abuse and war crimes taking place at Abu Ghraib prison. Australia had two citizens held without charge in an American offshore prison. And in an unprecedented spectacle for Australian Parliament, US President George Bush delivered a speech defending the invasion and acknowledging Australia’s commitment to US foreign policy. ‘You could hear a pin drop when he was speaking’, recalls Bob Brown, who was a Senator at the time. Brown sat silently in the chamber, waiting for the right moment to interject in an event that would make news around the world. ‘My heart was pounding, and I thought, ‘I can't do this’. All my old self-doubts came back. But I made myself. Up I got and spoke’. When Bush began speaking about human rights and stability in the Middle East, Brown rose to his feet and informed the President that the world would respect him if he were to abide by international law. Members across the House reacted with scorn and Brown was asked to leave. He remained. Brown and fellow Greens Senator Kerry Nettle would interject two more times throughout Bush’s speech.

In the CV of Bob Brown, the Bush interjection doesn’t usually feature anywhere near the top, largely because his many accomplishments don’t leave any room for it. But it’s significant for a number of reasons. In the House of Representatives that day, parliamentarians were expected to forget the criminality of the US invasion - and Australia’s complicity in it - and laud President Bush because it was the polite thing to do. The war crimes? This wasn’t the time. Looking back at the footage, you’d never know the backdrop to Bush’s speech was mass protest, war and suffering. The mood in the house appeared to be one of genuine excitement and anticipation, such is the seductive effect of power and dignitary. Bush reacted to Brown and Kettle’s second round of comments by making a joke, to which Coalition frontbenchers erupted with raucous laughter. It was an embarrassing display that showed, if ever there was any doubt, that it was all just a game. Nevertheless, it was Brown who was labelled ‘Embarrassing’ and ‘Un-Australian’ the next day. The event led to a hostile period for Brown which included threats of violence from sections of the right wing media. But this was an occasion that needed some form of resistance from Australia’s elected representatives. And Brown was one of the few with the foresight and conviction to do so. History judges the act accordingly.

Brown’s life journey to the frontline of Australian politics, where he was a Senator for 16 years and leader of the Australian Greens for 7, was not without its personal battles. His first foray into leadership happened by default at high school, where he became captain. ‘I had a trial run and was a misfit for any position of leadership. I couldn't make a speech. A couple of times I was shaking so much with nerves that I had to sit down’. Brown also grappled with being gay at a time when homosexual activity was a criminal offence. ‘It was very crushing. I internalised the stress and became quite sick’.

The stress led to crippling shyness and depression. ‘I think it was also part and parcel of being a deeply reflective person and realising none of us have the answers’. But the answers did come. Brown’s desire to help people was why he studied medicine and became a doctor, which led to a new perspective on the healing effect of nature. Brown’s inherent bond with nature meant he found his voice in taking action to protect it. ‘As a young doctor back in the 70s, I found that half the people coming to see me were basically suffering from stress - high blood pressure, rashes, stomach ulcers, skin problems and so on. And then I realised that the greatest resource for those folks - for all of us - is nature’.

Brown’s inherent bond with nature meant he found his voice in taking action to protect it. When he arrived in Tasmania in his early thirties, he found people thinking the way he did and immediately sent a card to his parents saying, “I’m home”. He joined the campaign to save the Franklin River and within a few years found himself as spokesperson for the campaign. ‘I was still very shy and the thought of speaking in front of people was still very daunting. But once I stopped and reflected, I was really campaigning for the river and not myself. Once I realised the spotlight wasn’t on me, it became much easier’. In the following years, the Wilderness Society would be set up in his kitchen. He would fast atop Mt Wellington to protest against a nuclear warship coming into Hobart. And he would make public the fact that he was gay. In 1996 he became the first openly gay member of the Parliament of Australia.

Brown’s honesty and conviction meant he always held a unique place in the world of frontline politics. Australian Parliament has no shortage of performance actors with a ‘born to rule’ mindset, one of whom recently completed a term as Prime Minister. ‘They don't stop and think about it. They just know they're right. And if there's a fault with the universe, it’s that the ladder of power is most easily climbed by those who are brutish, insensitive and uncaring. They've got no trouble treading on the hands and faces of people who are thoughtful, who are respectful, polite, who want to consider the other person's point of view. We tend to get leaders who are from the first mould and commentators from the second mould. We need to turn that around’.

In his book, Optimism, Brown quotes Bertrand Russell to explain the quirk in humanity that sees so many shallow men reach positions of power: ‘The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt’. For sensitive, reflective and intelligent people, the contemplation that comes with action can lead to deeper clarity and purpose. But it can also be crippling. For deep thinkers, Brown has some advice: ‘Get on with it. Don’t wait for someone else to take action. And don’t think anybody else will be better at it than you will be. The challenge for intelligent, sensitive folk is to take over’.

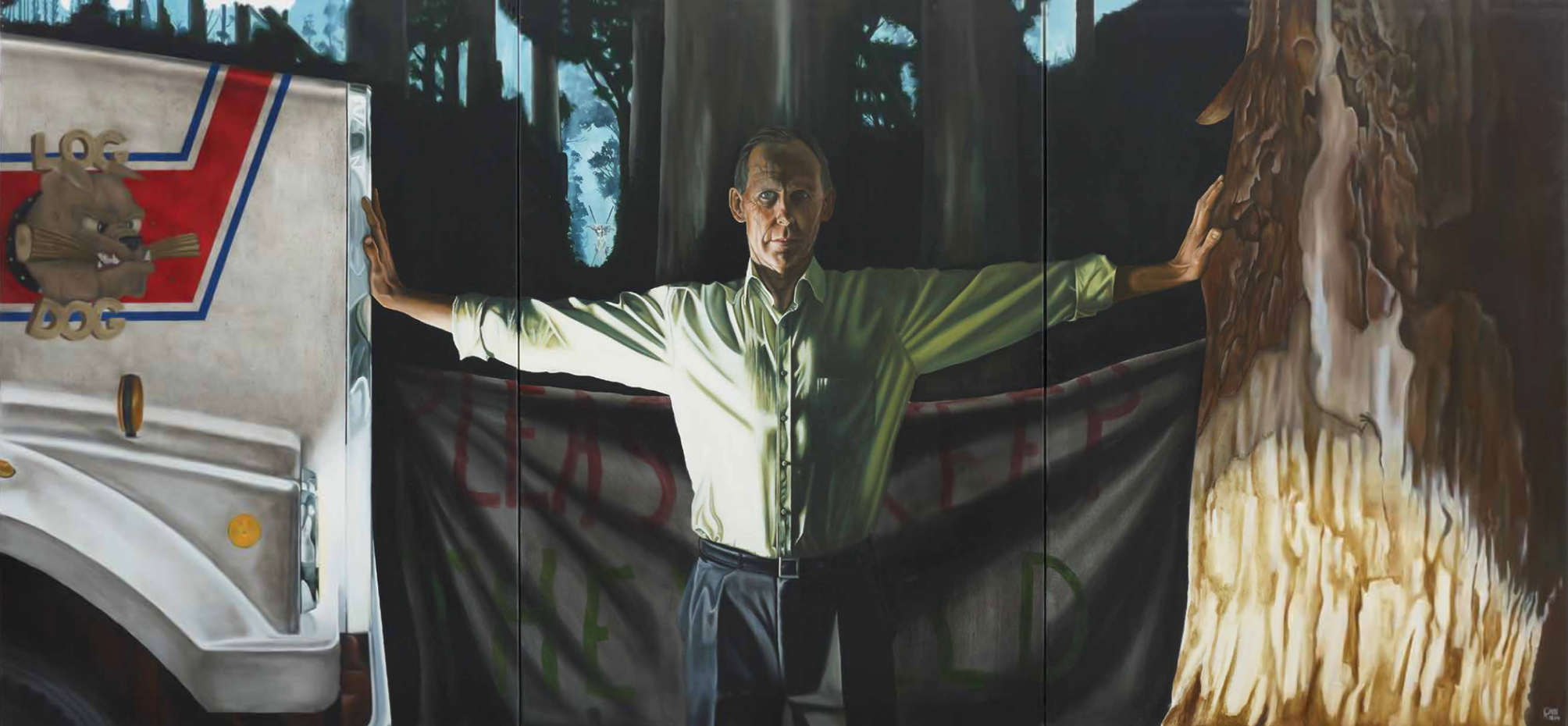

Having retired from the Senate in 2012, Brown has returned to where it all started, activism. At 77, he couldn’t be happier. ‘Life is long and in my experience it gets better. I’ve never been happier than being back as an activist’. The Bob Brown Foundation recently had a win to pause the destruction of an ancient patch of rainforest in takayna, Tasmania. 'We have 500 square km of magnificent forests, Aboriginal heritage and wildlife, yet 90 per cent is covered by mining leases. Spending time in that forest is absolutely crucial because it empowers us to speak for it'.